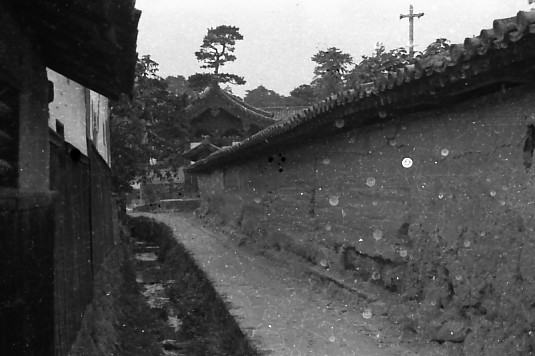

法隆寺土塀|The Earthen Wall of Hōryū-ji

撮影者:小城一郎(斑鳩の記憶データベース)

今回は、私の家の斜め向かいで生まれた詩人、池田克己の代表作「法隆寺土塀」です。

戦時中上海に移住していた池田克己は、終戦直前に上海を脱出し、北京で終戦を迎えますが、帰る途中の列車で共産党軍の襲撃にあい、二発の銃弾を受け重傷を負います。この事件で亡くなった同僚の骨を抱いて故郷に帰った満身創痍の彼を迎えた「土塀の胸」、六朝から続く歴史を受け止め、塗り込めてきた「土塀の胸」に彼自身の歴史も溶け込んでゆき、ただそこに「あるもの」として、引き受け、向かい合い、救いも浄化も求めることをせず生きようとする詩人の姿に胸を打たれました。

この一篇の詩に動かされ、私は、池田克己の資料を収集し、自宅を記念館として顕彰活動を始めました。

「法隆寺土塀」池田克己

帽子にたまつた雨水をはらい

靴底につもつた泥土を雜草になすり

頬につたう雫をぬぐい

龍田川からの一本道

土砂降りしぶく一本道

とうとう私はかえつてきた

松波木のむこうの綠靑いろに苔むした民家の屋根屋根 そのむ

こうの田圃の中を烟(*けむ)つて消える一本道

カタバミの小さな托葉と ヨナメの鋸葉 カヤツリ スズメノヒ

エや 綠の縫取した白帶の一本道

この道

十年ぶりの

私の中華民國からつづいている道

引揚船江ノ島丸の船底の 筵の上に腹這つて スクリユと機鑵

のガンガンにやられた頭が 九日七夜うろついていた——

Hの「支那彫刻史」と「三民主義と孫文」の稿成つた北平内一

區喜鵲胡同や

テリヤの亞里と鵞鳥と家鴨の戯れる 八十六本のタチアオイと

クチナシの匂いの中で 十八もポケットのついたダブダブの

爉衣で 包子を作つてくれたKの南京瑯玡路や

民國三十三年民國三十五年生まれの 私の原や道の オ

シメのひるがえつていた上海閘北寶昌道や

あれらの路地につづいている道

あれらの路地での夢幻夢想の

歲歲十年を一瞬にちぢめて

私の胸は動悸搏ち

私の頬は火照り

かなしみなく いかりなく

ためらいなく 痴愚なく 忘却なく

私はかえつてきた

日本が敗れたこと あれから四日目の華北の野で友が死んだこと

私の左腕貫通銃創

もうみんな帽子の雨水 靴の泥

この道は垣垣と

松並木のむこうから 田圃のむこうから 雜草

のむこうから

東支那海のむこうから

つづき

とうとう私はかえつてきた

土塀の外の蓑笠の田植

土塀の内の佛や伽藍

土塀の外の敗亡の今日の時

土塀の内の飛鳥や白鳳や天平の時

そして

私の中華民國十年の

さまざまな擧句の果ての

ただ一散にここに運んだ びしよ濡れの私の肉體を 支えて受ける

土塀の胸

この胸

かつて六朝を入れ

この胸 東トルキスタンに 健駄羅(ガンダラ)に 印度に 薩珊(ササン)に 東羅に

サラセンに

この胸さらに 希臘に アッシリヤに 埃及に

通い

この胸また

物部蘇我の 血しぶき浴び

あれらの渾沌未分の煙霧をととのえ

あれらの歴史や地理の激湍を塗りこめ

今は静かに土蜘蛛の這う

荒壁の土塀

私はかえつてきた

黄沙にまみれた服も脱がず

瓦礫と銹鐵の街に眼くれず

十年ぶりの中華民國からの一本道

とうとう私はかえつてきた

私の背の 私のあれからの時間の——

猫背になつて 黄浦灘(パンド)の屋上から 鋸形に黄昏の空を截るジャンクの帆布の列と 無數の人影を 眼しばたいて眺めていた私

狷介孤高の痩詩人路易士と「馬上侯」の壁間を埋める老酒の甕

の列を 卽ち一行一行の詩と數えていた私

單發の機上から 流れ行く家屋と人間 家畜と樹木 あの浙江

平原の大洪水をレンズに納めていた私

蟬時雨のような彈丸音の中で 皮膚病の苦力の尻をめくつて

膏藥をすりこんでいた私

あの時私は

何にかなしみ 何にいかり 何におどろきを發していたのであつた

か

歲歲十年

その茫茫の時間の極み

天津貨物廠跡の日僑収容所から引きずり出された貨物列車の 昏い

澱みの一隅で

堤防から投げつける小孩達の石礫の音を黙って聽いていた私には

もはや

かなしみなく いかりなく おどろきなく

帽子にたまつた雨水をはらい

靴底につもった泥土を雜草になすり

頬につたう雫をぬぐい

龍田川から一本道

土砂降りしぶく一本道

とうとう私はかえつてきた

私の中華民國の十年の

雜多矢鱈の

息せき切った一散の

昏昏迷迷の

肉體の前に立つ

荒壁

法隆寺土塀

| 用語 | 解説 |

|---|---|

| 法隆寺 | 奈良にある7世紀建立の寺院。現存する世界最古級の木造建築として知られる。仏教伝来の象徴。 |

| 龍田川 | 奈良県を流れる川で、紅葉の名所としても古来より多くの和歌に詠まれた。 |

| 江ノ島丸 | 終戦後、日本から中国・朝鮮などからの引き揚げ者を運んだ復員船の一つ。 |

| 喜鵲胡同 | 北平(現在の北京)の胡同(路地)名。詩人が滞在していた地名であり、戦中生活の記憶が凝縮されている。 |

| 瑯琊路 | 南京に実在した通り。中国生活の身近な記憶の象徴。 |

| 閘北宝昌道 | 上海の日本人街として栄えた地域。詩人の「故郷」とも言える場所。 |

| 六朝 | 中国南北朝時代の南方6政権を指す。仏教芸術の一大中心地でもあった。 |

| 健駄羅 | 古代インドとギリシャ文化の融合地。仏像の起源ともされる文化圏。 |

| 物部・蘇我 | 日本初期国家における権力抗争の中心。仏教受容をめぐって争った。 |

| 原・道 | 詩人・池田克己の子どもたちの名前。 |

Katsumi Ikeda (1908–1953) was a poet born in Yoshino, Nara Prefecture.

Today, the site of Katsumi Ikeda’s childhood home stands diagonally across

from my own house in Yoshino. It was this unexpected proximity that first

drew me to his work, and eventually led me to write and translate poetry

myself. I now maintain a small memorial room and blog to introduce his

poems to readers both in Japan and abroad.

Before and during World War II, he lived in Shanghai, where he worked in

photography and publishing, and was active in literary circles. As the

war worsened, he refused to continue writing propaganda for the Japanese

puppet government, stating that he could no longer write lies.

He eventually made a harrowing escape from Shanghai. While traveling by

train, Ikeda was shot twice during an ambush by Chinese Communist forces,

and a colleague who was with him was killed. Ikeda returned to Japan carrying

his colleague’s ashes, wounded in both body and spirit.

“The Earthen Wall of Hōryū-ji” is one of Ikeda’s most powerful works. It

is not simply a poem of return—it is a solemn testament to survival, to

the scars of history, and to the quiet presence of places that remember

more than we do.

The Earthen Wall of Hōryū-ji

Brushing rainwater off my hat,

rubbing the mud caked to my soles into the weeds,

wiping the droplets trailing down my cheeks—

along the straight path from the Tatsuta River,

a path blurred by a torrential downpour,

at last, I have returned.

Beyond the pine windbreak, roofs mossed over in green verdigris,

beyond them, a straight path vanishing into smoke over the rice fields.

A path embroidered with green—

with small stipules of wood sorrel,

serrated leaves of ground cherry,

sedges, barnyard millet—

a path of white bands stitched with green.

This road,

after ten long years,

leads from the Republic of China, within me.

Lying face-down on the straw mats

in the hold of the repatriation ship Enoshima Maru,

head pounded by the roar of screws and boilers—

for nine days and seven nights I wandered.

That alley in Beiping's Inner District 1, Magpie Lane,

where H completed his drafts on History of Chinese Sculpture

and The Three Principles of the People and Sun Yat-sen.

And Langya Road in Nanjing,

where K made me baozi—steamed meat buns—

in a loose apron with eighteen pockets,

amid eighty-six stalks of hollyhocks, the scent of gardenias,

and the play of Ari the dog, the geese, and the ducks.

And Baoshang Road, Zhabei, Shanghai,

where the diapers of my children, Hara and Michi—

born in the 33rd and 35th years of the Republic—

fluttered in the wind…

This road continues from those alleyways,

compressing ten years of visions and illusions

into an instant.

My chest pounds.

My cheeks burn.

With no sadness, no anger,

no hesitation, no foolishness, no forgetting—

I have returned.

Japan was defeated.

A friend died on the northern plains of China, four days later.

A gunshot wound pierced my left arm.

All of it now, like rainwater on my hat,

like mud on my shoes.

This road continues

from beyond the pine windbreak,

from beyond the rice fields,

from beyond the weeds,

from beyond the East China Sea—

and at last, I have returned.

The rice planters in straw capes outside the earthen wall,

the Buddhas and temple halls inside it.

The ruin and defeat of today outside the wall,

the ages of Asuka, Hakuhō, and Tempyo inside.

And here—

at the end of my ten long years in the Republic of China,

carried all the way to this place in one desperate breath,

my drenched body, now delivered,

is held and upheld

by the chest of the earthen wall.

This chest—

once embraced the Six Dynasties.

This chest—

reached out to East Turkestan,

Gandhara, India, Sassanid Persia, Eastern Rome,

and Saracen lands.

This chest—

touched Greece, Assyria, and Egypt.

And this chest, too—

was soaked in the blood spray of the Mononobe and Soga clans,

gathered the primordial mists of chaos,

sealed the torrents of history and geography—

and now lies still,

crawled upon by ground spiders,

an earthen wall of raw clay.

I have returned.

Still wearing my dust-covered clothes,

paying no mind to the rubble and rusted steel of the cities,

along this straight road from the Republic of China, after ten years—

at last, I have returned.

On my back—

the years since then.

I, hunched like a cat,

squinting at the sails of junks cutting the dusk sky

from the rooftop above the Huangpu banks.

I—

who counted the jars of old wine

filling the walls between recluse poet Luisi and the statue of the Horseback

Marquis,

as though counting lines of poetry.

I—

who captured from the air

flooded plains of Zhejiang,

the houses, the people, the livestock and trees,

all drifting past in the lens.

I—

who, under a shower of bullet fire like cicadas’ cries,

lifted the buttocks of a laborer with skin disease

to rub in a salve.

Back then—

What was it I mourned?

What did I rage against?

What wonder stirred in me?

Ten years.

The far reaches of that formless time—

in one dark corner of a freight car,

pulled from the ruins of the Japanese internment camp

at the site of the Tianjin Freight Depot.

There,

as the sound of stones thrown by local boys

struck the train’s embankment—

I listened in silence.

By then,

I had no sorrow,

no anger,

no surprise.

Brushing rainwater from my hat,

rubbing the mud from my soles into the weeds,

wiping the drip from my cheek—

the straight road from the Tatsuta River,

splashing under the downpour,

at last—

I have returned.

Before my body,

rushed and breathless,

out of that chaotic and disorderly decade

in the Republic of China—

there stands

the rough clay wall,

the earthen wall

of Hōryū-ji.

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Hōryū-ji | One of the oldest wooden buildings in the world, a temple in Nara founded in the early 7th century. |

| Tatsuta River | A river in Nara Prefecture, known for its scenic beauty and poetic associations. |

| Enoshima Maru | A Japanese repatriation ship used to bring citizens back from overseas after the war. |

| Magpie Lane | A hutong (alleyway) in Beiping (now Beijing), used here to evoke Ikeda's time in pre-Communist China. |

| Langya Road | A street in Nanjing, China. Its mention ties to Ikeda’s daily life in exile. |

| Zhabei, Baoshang Road | A district in Shanghai known for Japanese settlements before and during the war. |

| Six Dynasties | Refers to the period (220–589 CE) of Chinese history; important in Buddhist cultural transmission. |

| Gandhara | An ancient region in present-day Pakistan, significant for Buddhist art and Greco-Buddhist culture. |

| Mononobe and Soga clans | Rival aristocratic clans in early Japan; their conflict marked the spread of Buddhism. |

| baozi | A type of Chinese steamed bun filled with meat or vegetables. In the poem, the baozi made by "K" represents a gesture of kindness and domestic warmth amid the chaos of wartime life in China. |

| Gen and Michi | The names of Katsumi Ikeda’s children. |

Ikeda’s poem is not just a narrative of physical return from China to Japan—it

is a spiritual reckoning. Through images of mud, rain, weeds, and the tactile

reality of the dorohei (earthen wall), he stages a confrontation between

memory and the eternal. Each place-name and historical echo—from Gandhara

to the Sassanids, from ducklings in Nanjing to war wounds—forms a fragmented

cartography of his identity.

By contrasting the “outside” world of destruction and agriculture with

the “inside” world of Buddhism and continuity, he sets up a tension: modernity

and war have desecrated time, yet the wall endures. In standing before

it, soaked and broken, he finds no comfort—only presence.

There is no easy redemption in this poem. Rather, it is the act of facing—of

recognizing one’s unaltered material existence (“my drenched body”)—that

provides a kind of dignity. Hōryū-ji’s earthen wall becomes both a witness

and a mourner, an object that has “embraced the Six Dynasties” and now

embraces the poet.